A recent study found that historically redlined neighborhoods in Minneapolis are hotter than other areas of the city, disproportionately exposing communities of color to heat-related illness today.

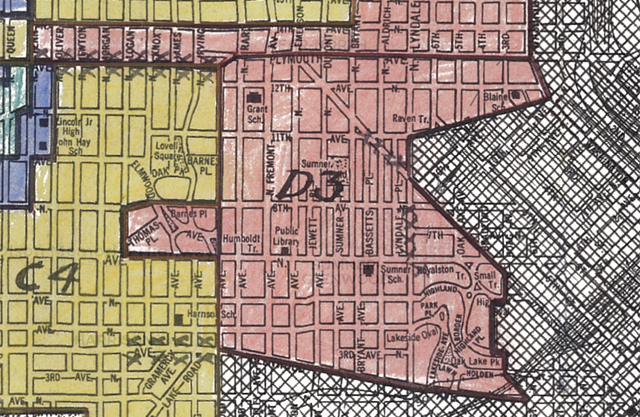

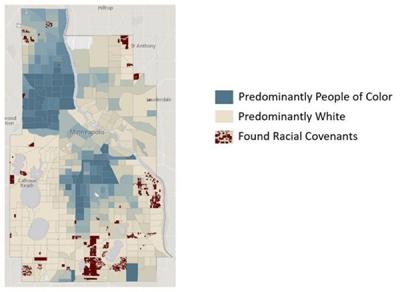

In the first half of the 20th century, Black residents in Minneapolis faced increasingly limited choices for where they could live. Discriminatory practices in real estate and lending included redlining and racial covenants, or deeds that included race-based restrictions on who could purchase the property. Redlining refers to a banking practice that restricted access to loans for properties in racially mixed and predominantly Black neighborhoods.

These practices changed the racial landscape of Minneapolis, effectively pushing Black residents into a few small areas while other neighborhoods became entirely white, and instigated a cycle of disinvestment in redlined communities. Though the federal Fair Housing Act in 1968 prohibited housing discrimination, this legacy has persisted in Minneapolis’s patterns of residential segregation and some of the worst racial disparities in the nation today.

A new study on the connections between residential segregation and the unequal impacts of climate change shows that many historically redlined neighborhoods contain the hottest areas in the U.S. today. Fewer trees, parks and green public spaces combined with more heat-trapping concrete buildings and asphalt roads mean that these neighborhoods retain more heat and provide less shade.

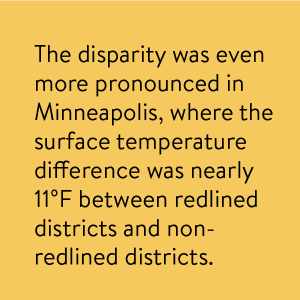

Comparing 108 urban areas on selected sunny days between 2014 and 2017, researchers found that former redlined neighborhoods were 5°F hotter on average than other parts of the same city. The disparity was even more pronounced in Minneapolis, where the surface temperature difference was nearly 11°F between redlined districts and non-redlined districts.

That "extra" heat creates a disproportionate risk of heat-related illness and mortality for communities of color, and is especially dangerous during summer heat waves, which are expected to increase due to climate change.

Recognizing these local differences and how they were created by design can help cities identify issues of environmental justice, understand who is most vulnerable, and work to reduce the risk of heat-related illnesses.

More information:

Map: Bloomberg News